"It arrived in the post, out of the blue, along with an offer to write and direct it as my first cinema film. Its literary style was as enigmatic as the manner of its arrival. Whilst set in England and written by an Englishman it was (aside from the rain) atypically English. More importantly it ripped off the rose-tinted glasses through which most people saw our mutual homeland. I suspect Ted never shared that Panglossian take on England."

—Mike Hodges, director of the original 1971 film adaptation of Ted Lewis’s Get Carter, writing in the Foreword to the new edition of the novel

From the films of Guy Ritchie and Martin McDonagh, which acknowledge their blueprints, to Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentleman series, in which Jack Carter is a character, the legacy of Ted Lewis’s novels has lived on in myriad ways, not the least of which through several generations of crime writers from either side of the pond.

Lewis’s most famous novel, Jack’s Return Home—later retitled Get Carter—is set in 1970 and tells the story of a London gangster named Jack Carter who has returned to his hometown in the industrial north of England to bury his brother, Frank. Everything about the way Frank died bothers Jack, but the brothers weren’t exactly friends. Jack, a ruthless business manager for London’s #1 crime syndicate, detested Frank’s weakness and hadn’t given his mild-mannered brother a second thought since he left home. That is, until he was murdered. It is there that Lewis put Jack Carter on a hard road to redemption, one where he will decide that it’s worth sacrificing a life’s work for a chance to “make things right.”

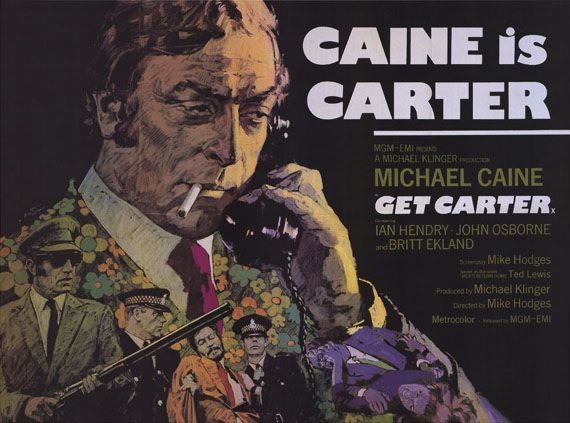

Since its initial publication Get Carter has been adapted into a motion picture no fewer than three times: Mike Hodges’s seminal 1971 gangster film starring Michael Caine, Ian Hendry and John Osborne; the 1972 “Blaxsploitation” film Hit Man, starring Pam Grier and Bernie Casey; and Warner Brothers’s 2000 Seattle-based remake starring Sylvester Stallone, Alan Cumming, and Mickey Rourke.

Of his other novels, the twisted and brilliantly plotted blackmail story Plender (1971) has also been adapted to the big screen, in this case a very well-received French film, Le Serpent, released in 2006.

In the celebrated 1970s British detective TV series The Sweeney, the two featured detectives are not accidentally named Jack Reagan and George Carter. Lewis never saw a penny from that very successful show and according to the British author and Lewis biographer Nick Triplow, it bothered the writer immensely.

Then there is his impact on writing. The late noir pioneer Derek Raymond openly declared Lewis’s influence on his own work, as has modern master David Peace. There is something of Get Carter to be seen in the work of Northern Irish writer Stuart Neville, especially in his award-winning novel, The Ghosts of Belfast. Not to forget, there are also the wonderful novels of Jake Arnott, with their openly gay underworld operators, whose originals were represented by Lewis in many of his novels. This last detail is one that clearly separates Lewis from many of his peers, especially from the United States.

So why, despite all of the people and media his work influenced, is the author yet unknown in North America? The answer is not all that surprising.

The Mike Hodges adaptation of Get Carter is now undisputed as a classic of modern British cinema, but the truth is, it never did well in its limited U.S. theatrical release. The film had extremely limited distribution and never had enough market share to catch on, despite several positive notices. There was little to no mention of Ted Lewis’s novel in any of the later adaptations. Nor was the novel well received in the U.S. In fact, it wasn’t really received at all. At the time of writing this, I have yet to find a review of the novel from its original publication by Doubleday in 1970.

Certainly Lewis’s early death had a lot to do with his obscurity. Ted Lewis died in 1982 of alcohol-related illness. He was only 42. His last book, GBH, had just been published as a paperback original in the UK. It was adorned with minimal (and inaccurate) copy and the book went unnoticed, the author’s death marginally noted. Most of his books drifted out of print in the U.K.

In the 1990s the U.K. saw a wave of interest in Mod fashion, film, music, and the bygone Soho district of late 1960s London. Get Carter, first the film and then the novel, reemerged as iconic. The likes of Quentin Tarantino named it his all-time favorite British film. Writers and critics who had been influenced by the book and film quickly jumped at the opportunity to reestablish Lewis and his works. Both the film and the book started cropping up on “Best of” and Top 10/25/100 style lists of the century’s formative literary and cinematic works.

It was in this time that the likes of the aforementioned Derek Raymond, who himself had a substantial resurgence in the 1990s, cited Lewis as among the first and most influential British crime novelists. David Peace described Get Carter as “the finest British crime novel I’ve ever read.” Beyond the page, Get Carter and one of its two prequels, Jack Carter’s Law, have both been adapted into radio plays by the BBC. The enigmatic author has received numerous posthumous profiles on TV and radio, and is even the subject of a biography currently being written by crime writer Nick Triplow. Triplow has written a short sketch of the enigmatic Lewis’s life as an afterword to the Syndicate Books edition of Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon.

All this is to say that Ted Lewis will come as something of a revelation to U.S. readers. There is nothing cliché or cartoonish about his characters. The violence perpetrated isn’t easily brushed off. It is legitimate—palpable and consequential, just like the real stuff. There are no clean hands in a Lewis novel. No paladin cops with deadly aim. Justice and honor are warped, twisted things, and they and everyone involved is bent to the will of the powerful and wealthy, disposable at a whim. These are people at the fringes, willing to do anything for the perception of respect, self or otherwise. The tragic pursuit of every Lewis character is dignity, and perhaps nowhere is that paradigm more evident than in a tough lad from the north counties, who for years placed his trust in tailored mohair suits and gold cuff links. Ted Lewis was very good at writing bad people.

You could argue that his legacy and influence on popular culture is to the second half of the 20th century what Hammett and Chandler’s was to the first half. Perhaps James M. Cain is more apropos. It’s time Lewis was recognized for the work that so many have built upon.